The lithium-ion battery has transformed modern life, powering everything from smartphones to electric vehicles to

grid-scale energy storage. But despite continuous improvement over three decades, lithium-ion technology faces

fundamental limitations that constrain performance. A new contender promises to shatter those limitations: solid

state batteries that replace flammable liquid electrolytes with stable solid materials. Major automakers and tech

giants are investing billions in this technology, with some claiming it will revolutionize energy storage. But how

do solid state batteries actually compare to today’s lithium-ion technology, and when will they become available?

Understanding How Batteries Work

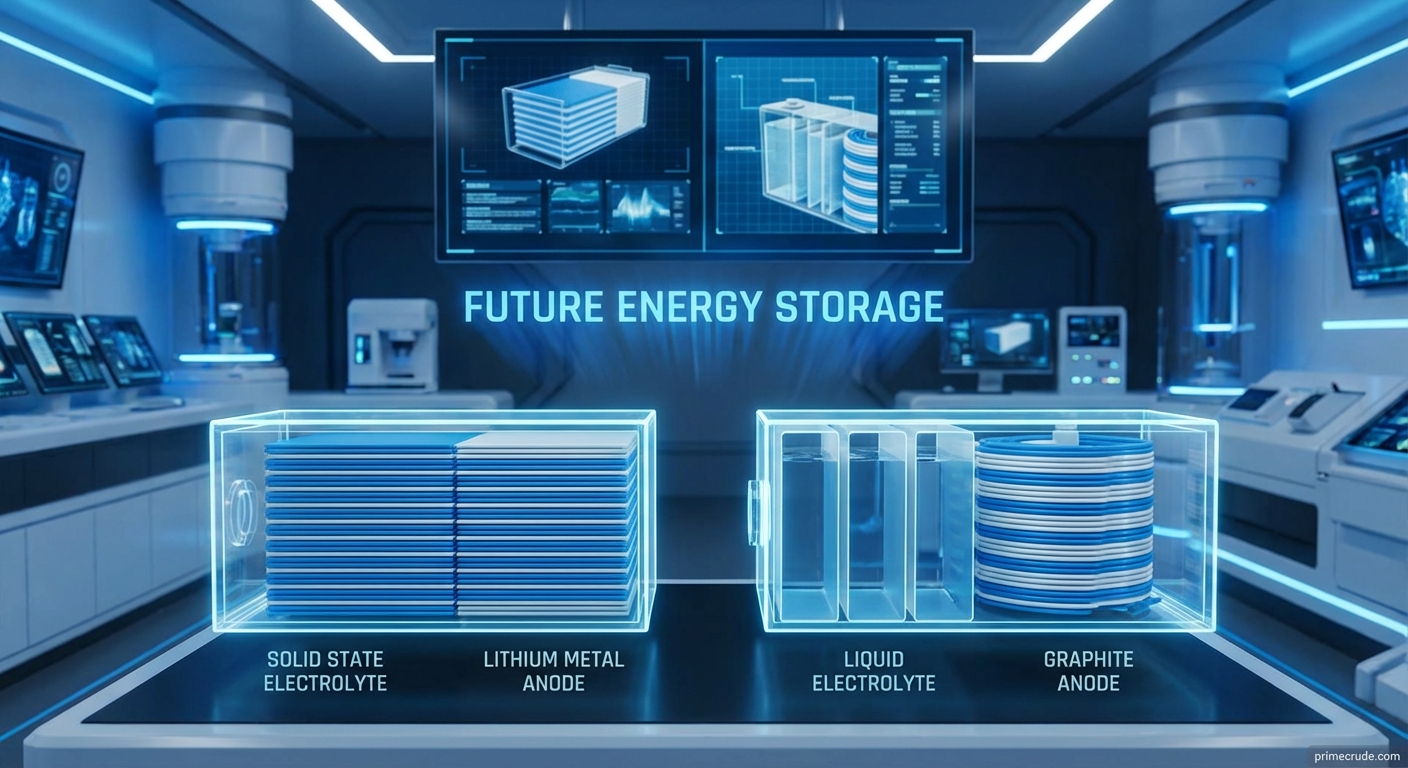

Before comparing technologies, understanding basic battery operation helps clarify what makes solid state batteries

different. All rechargeable batteries work by moving ions between two electrodes—the anode and cathode—through a

medium called the electrolyte. During discharge, ions flow one direction; during charging, they flow back.

In today’s lithium-ion batteries, lithium ions shuttle between a graphite anode and a metal oxide cathode through a

liquid or gel electrolyte. This liquid electrolyte, typically a lithium salt dissolved in organic solvents, conducts

ions efficiently but has significant drawbacks.

The Solid State Difference

Solid state batteries replace the liquid electrolyte with a solid material—ceramic, glass, or polymer—that conducts

ions while remaining mechanically stable. This seemingly simple change enables fundamental improvements in energy

density, safety, and charging speed that liquid electrolytes can’t match.

The solid electrolyte allows use of different electrode materials than liquid systems can accommodate. Most notably,

solid state designs often pair with pure lithium metal anodes rather than graphite. Lithium metal holds vastly more

energy per gram than graphite, driving the most significant performance improvements solid state batteries offer.

Energy Density: More Power, Less Weight

The most compelling advantage of solid state batteries is their potential for much higher energy density—the amount

of energy stored per unit weight or volume. This metric matters enormously for electric vehicles, where battery

weight directly limits driving range.

Current lithium-ion batteries achieve roughly 250-300 Wh/kg (watt-hours per kilogram) at the cell level. The best

commercial cells approach 350 Wh/kg. These figures have improved steadily over the years but face theoretical limits

as graphite anodes and available cathode materials constrain further gains.

Solid State Energy Density Potential

Solid state batteries with lithium metal anodes could achieve 400-500 Wh/kg in near-term designs, with theoretical

potential exceeding 700 Wh/kg as technology matures. This represents 50-100% improvement over current lithium-ion

technology.

What does this mean practically? An electric vehicle with today’s 300-mile range battery pack could achieve 450-600

miles with a solid state battery of the same size and weight. Alternatively, the same range could be achieved with a

smaller, lighter, cheaper battery pack.

Safety Improvements

The liquid electrolytes in lithium-ion batteries are flammable and can catch fire if cells are damaged, overheated,

or improperly manufactured. High-profile battery fires in phones, laptops, and electric vehicles have raised safety

concerns despite their relative rarity.

Battery makers manage fire risk through extensive safety systems—thermal management, cell monitoring, pressure

relief, and fire-resistant enclosures. These systems add weight, cost, and complexity while not eliminating risk

entirely. The liquid electrolyte remains fundamentally flammable.

Solid State Safety Advantages

Solid electrolytes, by nature, don’t catch fire. Most solid electrolyte materials are non-flammable and can

withstand high temperatures that would ignite liquid alternatives. This intrinsic safety simplifies system design

and could eventually reduce the elaborate protection systems lithium-ion batteries require.

Solid state batteries also resist the “thermal runaway” cascade where one failing cell heats neighbors and triggers

a chain reaction. Without flammable liquid to spread flames, damage tends to remain localized. This characteristic

makes solid state batteries especially attractive for densely packed applications like aircraft and confined spaces.

Charging Speed Potential

Charging time represents one of electric vehicles’ biggest consumer complaints. Fast charging stations can add

significant range in 20-30 minutes, but that’s still far slower than filling a gas tank. Battery chemistry limits

charging speed because pushing ions too fast causes degradation and safety risks.

Liquid electrolyte lithium-ion cells face particular challenges at low temperatures, where the electrolyte becomes

sluggish and lithium can plate onto electrodes in metallic form—a serious safety and degradation issue. Cold weather

charging must be done slowly or with battery heating.

Faster Solid State Charging

Certain solid electrolyte materials demonstrate exceptionally fast ion transport, enabling very rapid charging

without the degradation that liquid systems suffer. Some prototype solid state cells have demonstrated charging from

empty to 80% in under 15 minutes without overheating or accelerated aging.

The potential for 10-minute charging would transform electric vehicle usability, making “refueling” experiences

comparable to gasoline vehicles. Achieving this in production vehicles while maintaining other performance

characteristics remains an engineering challenge, but the fundamental chemistry supports the possibility.

Current Limitations and Challenges

If solid state batteries were simply better across the board, they would have replaced lithium-ion years ago.

Significant technical challenges explain why production remains limited despite decades of research.

Manufacturing solid state batteries at scale proves extremely difficult. The solid electrolyte materials must be

processed precisely to ensure good contact with electrodes throughout the cell. Air and moisture sensitivity

requires controlled manufacturing environments. These factors make production far more complex and expensive than

liquid electrolyte cells.

The Interface Problem

The biggest technical challenge involves interfaces between solid materials. In liquid systems, the electrolyte

conforms perfectly to electrode surfaces, maintaining contact as materials expand and contract during charge and

discharge. Solid materials can’t flow, leading to contact loss and performance degradation over time.

Researchers have spent years developing solutions: softer solid electrolytes, engineered interface layers, and novel

manufacturing techniques. Progress has been substantial but the problem isn’t fully solved. Many prototype cells

show excellent initial performance that degrades faster than liquid lithium-ion equivalents.

Cycle Life Concerns

Related to interface issues, some solid state designs show concerning cycle life—the number of charge/discharge

cycles before significant capacity loss. Electric vehicle batteries should last thousands of cycles over 10-15

years. Early solid state prototypes sometimes showed substantial degradation after hundreds of cycles.

Recent developments have improved cycle life dramatically. Some manufacturers now claim cells meeting or exceeding

lithium-ion durability standards. Whether these claims hold up in real-world production and use remains to be proven

at scale.

Manufacturing and Cost Challenges

Lithium-ion batteries benefit from 30 years of manufacturing optimization. Enormous factories produce cells at high

speeds with remarkable consistency. This mature manufacturing base explains why lithium-ion prices have fallen

roughly 90% since 2010.

Solid state batteries lack this manufacturing heritage. New production techniques must be developed, equipment

designed and built, and processes optimized. This learning curve means early solid state batteries will cost

substantially more than equivalent lithium-ion cells.

Cost Reduction Trajectories

Industry projections suggest solid state batteries might initially cost 2-5 times as much as lithium-ion

equivalents. Over time, manufacturing learning and scale economics should reduce this premium. Some analysts project

cost parity within 10-15 years of mass production start; others are more skeptical.

The raw materials for solid state batteries vary depending on specific chemistry. Some designs use abundant, cheap

materials that should become cheaper than lithium-ion equivalents at scale. Others rely on specialized materials

that may face supply constraints.

Who’s Developing Solid State Batteries?

The solid state battery race involves major corporations, well-funded startups, and national laboratories worldwide.

Billions of dollars in investment reflect the perceived importance of this technology.

Toyota holds more solid state battery patents than any other company and has been working on the technology for over

a decade. The company has announced plans for limited solid state battery vehicles by the mid-2020s, though

timelines have slipped repeatedly.

Other Major Players

QuantumScape, backed by Volkswagen, has received enormous attention and investment for its ceramic solid electrolyte

technology. The company’s claims of breakthrough performance have attracted both enthusiasm and skepticism, with

independent verification still limited.

Samsung SDI, SK Innovation, and CATL—major Asian battery makers—all have active solid state programs. Their existing

manufacturing expertise should help translate laboratory advances to production more quickly than pure research

organizations.

Solid Power, partnered with BMW and Ford, has demonstrated pouch cells manufactured on modified lithium-ion

production equipment—an approach that could accelerate commercialization by leveraging existing infrastructure.

Timeline Expectations

When will solid state batteries actually be available? This question has proved embarrassingly difficult for the

industry, with announced timelines repeatedly pushed back as technical challenges proved more stubborn than

expected.

Most informed observers expect limited commercial availability in the mid-to-late 2020s, initially in premium

applications like high-end electric vehicles where buyers will pay significant premiums for cutting-edge technology.

Volume production for mainstream vehicles likely waits until the early-to-mid 2030s.

Near-Term Milestones

Several companies have announced pilot production lines scheduled for 2024-2026. These facilities will produce

relatively small volumes—perhaps thousands or tens of thousands of cells per year compared to the billions of

lithium-ion cells manufactured annually. Early production serves validation and refinement rather than commercial

supply.

Watch for announcements of automotive OEMs actually using solid state batteries in production vehicles—not concept

cars or demonstrations. This milestone, when it occurs, will mark the transition from research to commercialization.

What This Means for Consumers

For consumers considering electric vehicles or other battery-powered products, solid state technology represents a

promising but not yet practical option. Buying decisions today should be based on available lithium-ion technology

rather than waiting for solid state alternatives.

Current lithium-ion electric vehicles offer excellent performance that continues improving. Battery warranties

typically cover 8-10 years, by which time owners will likely be considering vehicle replacement anyway. The idea of

waiting years for solid state technology makes little practical sense.

Future Vehicle Considerations

If considering an electric vehicle purchase in the late 2020s or beyond, solid state options may be available in

premium segments. Early adopters will pay substantial premiums for cutting-edge technology. Waiting for second or

third generation products typically provides better value as manufacturers work out issues.

The broader electric vehicle market will likely use lithium-ion batteries for years even after solid state

alternatives appear. Manufacturers won’t instantly abandon optimized, cheap lithium-ion technology for expensive new

alternatives. Expect gradual transition rather than sudden replacement.

Beyond Electric Vehicles

While electric vehicles drive most solid state battery investment, other applications could benefit significantly.

Consumer electronics, grid storage, aerospace, and medical devices all have specific requirements that solid state

characteristics might address.

For consumer electronics, solid state’s higher energy density means longer-lasting devices without size or weight

increases. Improved safety matters for devices carried against bodies or used in enclosed spaces. Fast charging

appeals to users tired of overnight charging requirements.

Grid-Scale Storage

Grid-scale storage presents a more complex case. Solid state batteries’ safety advantages matter when thousands of

cells are packed together. However, energy density matters less when space isn’t constrained. Cost per kilowatt-hour

matters most for grid applications, making expensive solid state technology less competitive until prices decline

substantially.

Aviation and aerospace applications particularly value high energy density and safety. Even premium costs are

acceptable if batteries enable new capabilities. These applications may see earlier adoption than cost-sensitive

markets.

The Competitive Landscape

Solid state batteries aren’t the only next-generation technology pursuing better performance. Lithium-ion

improvements continue with silicon anodes, high-nickel cathodes, and manufacturing refinements. Alternative

chemistries like sodium-ion offer different tradeoffs for different applications.

This competitive pressure means solid state batteries must deliver on their promises rather than benefit from a lack

of alternatives. If lithium-ion continues improving fast enough, the premium for solid state may never prove

justified for cost-sensitive applications.

A Balanced View

The most likely outcome is segmented adoption rather than wholesale replacement. Solid state batteries will dominate

where their advantages—safety, energy density, fast charging—matter most and cost premiums are acceptable.

Lithium-ion will persist where its mature manufacturing and lower costs provide adequate performance at lower

prices.

This coexistence mirrors the current battery landscape, where different lithium-ion chemistries serve different

applications based on priority tradeoffs. Chemistry choice has always been about matching technology to requirements

rather than seeking universal solutions.

Conclusion

Solid state batteries offer compelling potential advantages over lithium-ion technology: higher energy density,

improved safety, faster charging, and longer lifespan. These improvements, if achieved in production, would

significantly advance electric vehicles and other applications.

However, substantial challenges remain in manufacturing, cost, and long-term reliability. The technology is

approaching commercialization after decades of research, but the path to mass production and cost competitiveness

will take additional years.

For consumers, solid state batteries represent a reason for optimism about the future of electric vehicles and

portable electronics rather than a reason to delay purchases today. Current lithium-ion technology delivers

excellent performance that solid state will eventually enhance rather than make obsolete.

The solid state battery revolution is coming, but like most revolutions, it will unfold over years rather

than arriving overnight. Patience and realistic expectations serve observers better than hype-driven

excitement.