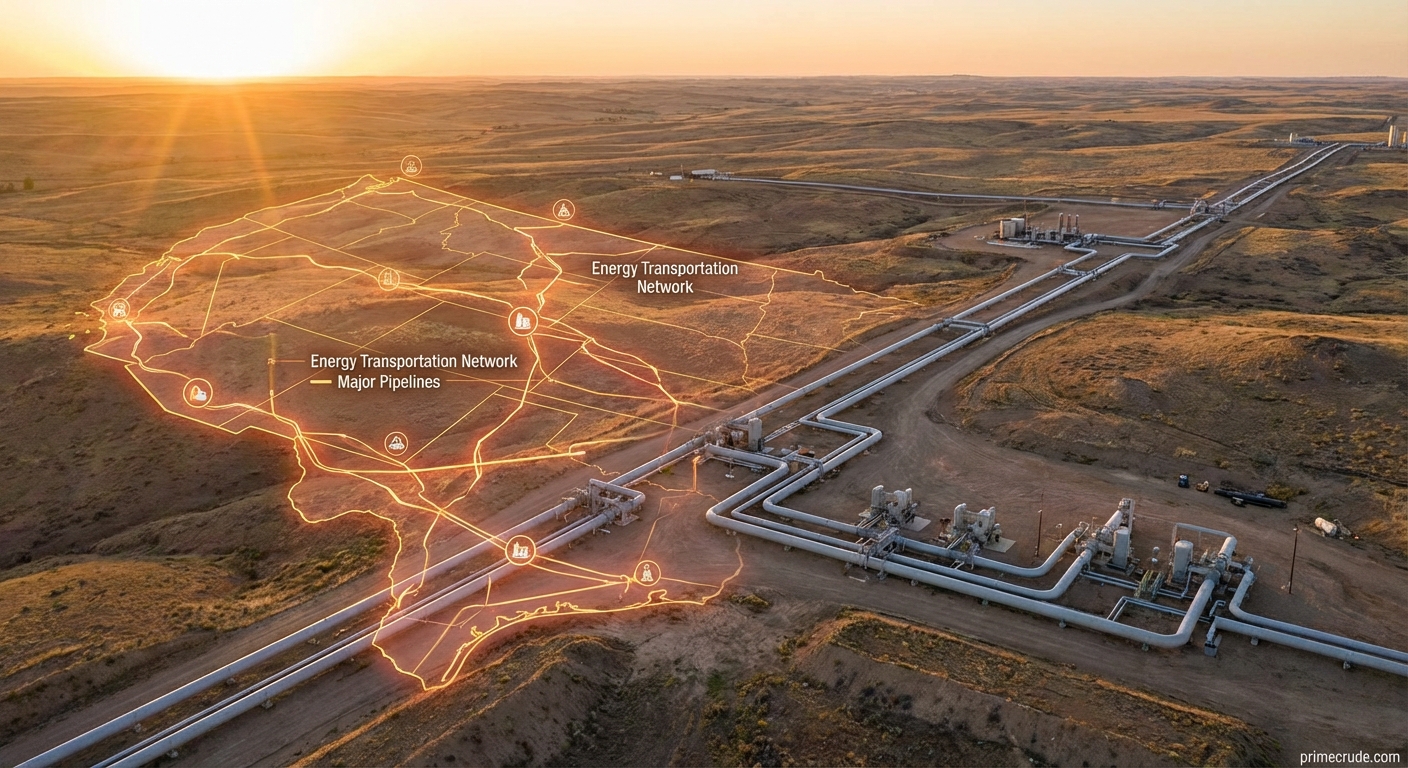

Beneath American highways, farms, and cities lies an invisible network of steel arteries carrying the lifeblood of

the modern economy. Over 190,000 miles of liquid petroleum pipelines crisscross the United States, moving roughly 15

million barrels of crude oil and refined products daily from production zones to refineries and distribution

centers. This infrastructure, mostly built decades ago and operating largely out of sight, represents one of the

largest private infrastructure investments in human history. Understanding how this pipeline network functions—where

it runs, who operates it, how oil moves from Texas wells to East Coast gas stations—reveals the physical reality

underlying abstract commodity markets. The pipeline map of America tells the story of a century of energy

development and raises questions about how this aging network will evolve as energy transitions reshape

transportation fuel demand.

The Scale of the Pipeline Network

America’s pipeline network dwarfs any other transportation infrastructure. The roughly 190,000 miles of liquid

petroleum pipelines exceed the combined length of the U.S. Interstate Highway System and all Class I railroad track.

Add natural gas pipelines, and the total exceeds 2.6 million miles.

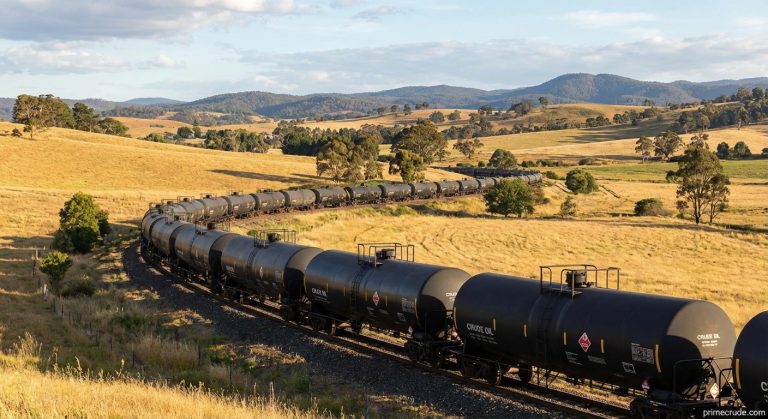

This infrastructure moves about 70% of all crude oil and petroleum products, with the remainder traveling by rail,

barge, and tanker truck. Pipelines offer the lowest-cost transportation per barrel-mile, making them the default

choice for high-volume, consistent flows.

Pipeline Categories

Different pipeline types serve different functions. Crude oil pipelines move unrefined petroleum from production

areas to refineries. Product pipelines carry refined fuels like gasoline, diesel, and jet fuel from refineries to

terminals and distribution points. Some pipelines carry both, switching between batches.

Pipeline economics favor moving uniform products long distances. Startup, shutdown, and product segregation costs

mean pipelines work best for steady flows rather than intermittent transport.

Major Crude Oil Pipeline Systems

Several major pipeline systems dominate crude oil transportation, connecting production basins to refining centers.

Understanding these systems illuminates how oil flows across the country.

The pipeline network connecting the Permian Basin in West Texas to Gulf Coast refineries has grown dramatically to

handle the shale production boom. Lines like the Permian Express and Cactus systems move over 2 million barrels

daily from the most productive oil region in America.

The Cushing Hub

Cushing, Oklahoma serves as the crossroads of American oil pipelines, where lines from multiple producing regions

converge and redistribute to refineries across the mid-continent. The crude futures contract that sets WTI prices

specifies delivery at Cushing, making this small Oklahoma town the physical center of American oil pricing.

Tank storage at Cushing exceeds 90 million barrels capacity, though in the infamous negative price event of April

2020, even this vast capacity nearly filled, contributing to prices briefly falling below zero.

| Major Pipeline System | Route | Approximate Capacity |

|---|---|---|

| Permian Express | Permian Basin to Gulf Coast | ~850,000 bpd |

| Dakota Access (DAPL) | Bakken to Illinois | ~750,000 bpd |

| Keystone System | Canada to Gulf Coast/Midwest | ~600,000 bpd |

| Capline | Gulf Coast to Midwest | ~1.2 million bpd |

| Trans Mountain | Alberta to Pacific Coast | ~890,000 bpd (expanded) |

Product Pipeline Networks

Refined products—gasoline, diesel, jet fuel—move through a separate pipeline network from refineries to market

areas. This network ensures that fuel reaches the 150,000 gas stations across America reliably and economically.

The Colonial Pipeline is the largest refined products pipeline, running 5,500 miles from Houston-area refineries to

the Northeast, delivering about 100 million gallons daily. When ransomware attacked Colonial in 2021, panic buying

emptied gas stations across the Southeast, demonstrating the pipeline’s importance.

Batching Different Products

Product pipelines move different fuels sequentially in “batches” with minimal mixing. Gasoline follows diesel

follows jet fuel through the same pipe. Interface material at batch boundaries—called “transmix”—is separated and

reprocessed at terminals.

Sophisticated systems track batch locations through the pipeline, scheduling delivery to correct destinations. A

terminal might receive its gasoline batch at 3 AM, diesel at 7 AM, and premium gasoline at noon—all through the same

pipe.

Pipeline Operations

Pipelines operate through pump stations spaced along their routes. Electric motors or turbines drive pumps that

maintain oil flowing at 3-8 miles per hour. Crude traveling from North Dakota to Louisiana might take 2-3 weeks to

complete the journey.

Control centers monitor entire pipeline systems around the clock. Operators track pressure, flow rates, and pump

status, responding to deviations that might indicate leaks or equipment problems. SCADA systems automate much of

normal operation while providing alerts for abnormal conditions.

Leak Detection and Safety

Modern pipelines incorporate multiple leak detection methods: computational systems compare inlet and outlet

volumes; pressure sensors detect sudden drops; acoustic sensors listen for leak sounds; regular aerial and ground

patrols inspect rights-of-way.

Despite these measures, leaks occur. The pipeline industry reports releasing roughly 3 million gallons of oil

annually through spills—concerning but representing a tiny fraction of the billions of barrels transported.

Pipeline Economics

Pipeline transportation costs typically run $1-5 per barrel depending on distance and competition. This compares

favorably to rail transport at $5-15 per barrel or truck transport at $20+ per barrel for equivalent distances.

This cost advantage makes pipelines the preferred method for high-volume, predictable flows. The investment required

to build pipelines—often billions of dollars for major projects—is justified by decades of transportation cost

savings.

Tariff Regulation

Many crude oil pipelines operate as common carriers, required to transport oil for any shipper at published tariff

rates regulated by the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC). This regulatory framework ensures access and

prevents monopolistic pricing.

Some pipelines operate as private carriers, owned by or contracted to specific producers or refiners. These private

systems lack common carrier obligations but also lack tariff regulation.

Pipeline Controversies

Pipeline projects often face significant opposition from environmental groups, indigenous communities, and affected

landowners. The Keystone XL and Dakota Access pipelines became national flashpoints over climate policy, indigenous

rights, and energy development.

Opponents argue that pipelines lock in fossil fuel infrastructure for decades, cross sensitive lands and waters

without adequate protections, and benefit communities far from where risks fall. Supporters counter that pipelines

are safer than alternative transportation and that energy demand makes some transport method necessary.

Regulatory and Legal Challenges

Pipeline permitting requires navigating multiple federal, state, and local approvals. Environmental reviews under

the National Environmental Policy Act can take years. State-level approvals vary widely in stringency and political

context.

Legal challenges from environmental groups, tribes, and landowners have delayed or stopped major projects. The

Keystone XL cancellation and ongoing Dakota Access litigation illustrate the legal obstacles pipelines face.

Aging Infrastructure

Much of America’s pipeline infrastructure was built decades ago. Some pipelines date to the 1940s and 1950s. While

replacement and maintenance have extended service life, aging steel and joints present reliability and safety

concerns.

Replacement cycles are measured in decades. Pipelines are designed for 50-100 year lifespans with proper

maintenance. However, increased scrutiny following high-profile spills has accelerated inspection and replacement

programs.

Maintenance and Investment

Pipeline operators collectively invest billions annually in maintenance, inspection, and upgrades. Inline inspection

tools called “smart pigs” travel through pipelines detecting corrosion, cracks, and other defects. Remediation

programs address identified problems.

Regulatory requirements for pipeline integrity management have increased following major incidents. The Pipeline and

Hazardous Materials Safety Administration (PHMSA) sets and enforces safety standards.

Future of Pipeline Infrastructure

As electric vehicles reduce gasoline demand and energy transitions reshape fuel markets, pipeline infrastructure

faces uncertain long-term futures. Some pipelines may see declining utilization; others may repurpose for different

products.

Hydrogen and carbon dioxide transport could provide new uses for existing pipeline corridors. Converting natural gas

pipelines to hydrogen is technically challenging but under study. CO2 pipelines for carbon capture and storage are

growing.

Continued Near-Term Need

Despite long-term uncertainty, pipelines remain essential for the foreseeable future. Even ambitious electrification

scenarios show petroleum demand persisting for decades for aviation, shipping, petrochemicals, and regions slow to

electrify.

Existing pipelines will continue operating as long as economic to do so. New capacity additions have slowed but not

stopped entirely as operators evaluate long-term demand.

Mapping the Network

Public mapping resources provide visibility into pipeline locations. The National Pipeline Mapping System (NPMS)

offers interactive maps showing pipeline routes. State regulatory agencies maintain more detailed local maps.

Landowners can access pipeline location information to understand what crosses their property. “811”

call-before-you-dig services prevent excavation damage to buried pipelines.

Security Considerations

Some pipeline location details are restricted for security reasons. Critical infrastructure protection guidelines

limit public disclosure of information that could assist attacks. The Colonial Pipeline ransomware incident

highlighted cyber vulnerabilities.

Physical security includes fencing at pump stations, surveillance cameras, and patrol programs. However, the vast

extent of pipeline networks makes complete physical security impossible.

Conclusion

America’s oil pipeline infrastructure represents an engineering marvel and economic foundation that most people

never see or consider. Over 190,000 miles of steel pipe move the equivalent of a fleet of tanker trucks every

minute, delivering crude to refineries and fuels to consumers at costs no other transportation method can match.

This network faces challenges: aging infrastructure requires investment, new projects face fierce opposition, and

long-term demand uncertainty clouds investment decisions. Yet pipelines will remain essential for American energy

supply for decades regardless of transition pace.

Understanding the pipeline network—where it runs, how it operates, who controls it—reveals the physical

infrastructure that connects abstract commodity markets to the gasoline that ends up in your car’s tank.

The steel veins carrying oil beneath American soil represent a century of infrastructure investment,

engineering achievement, and economic foundation—invisible but essential to daily life.

-768x419.png)