Every time oil prices spike or natural gas futures plummet, someone is making money from the volatility.

Professional energy traders at banks, hedge funds, and commodity trading houses have built careers around

anticipating and profiting from price swings that leave ordinary consumers frustrated at the pump. The energy

trading world operates largely invisible to the public, yet its participants influence the prices we all pay for

fuel, heating, and electricity. Understanding how these traders operate—their strategies, their tools, and the risks

they manage—reveals a sophisticated industry that serves essential functions while generating enormous profits from

market turbulence. Whether prices go up or down, skilled traders find ways to profit, while the unlucky or

unprepared can lose fortunes in minutes.

The Energy Trading Ecosystem

Energy trading occurs across multiple interconnected markets. Physical trading involves buying and selling actual

barrels of oil, tanker loads of LNG, or pipeline capacity for natural gas. Financial trading uses

derivatives—futures, options, and swaps—that derive their value from underlying physical commodities without

necessarily involving physical delivery.

Major participants include oil companies trading their own production and hedging price risk, utilities securing

fuel supplies at predictable costs, banks providing capital and market-making services, and hedge funds speculating

on price movements. Each participant has different objectives, time horizons, and risk tolerances that together

create liquid markets.

Physical vs. Financial Trading

Physical traders arrange actual delivery of commodities. A trader might buy crude oil from Saudi Arabia, arrange

shipping to Houston, and sell it to a refinery—earning the spread between purchase and sale prices. This business

requires logistics expertise, relationships with producers and consumers, and often significant infrastructure.

Financial traders, by contrast, rarely take physical delivery. They buy and sell contracts that will be closed out

before delivery dates, profiting from price movements rather than physical commodity flows. Many successful trading

operations combine both approaches, using physical assets to inform and support financial positions.

Making Money When Prices Rise

The most straightforward trading strategy is buying low and selling high. Traders who correctly anticipate price

increases can take “long” positions—buying futures contracts or physical commodities—that appreciate as prices rise.

The profit equals the price increase multiplied by position size.

Going long during the 2020-2021 oil recovery generated enormous profits. Traders who bought when prices crashed

during the pandemic and held through the recovery saw crude oil prices more than triple from their lows. Those with

the conviction and capital to hold large positions through the uncertainty earned returns few other investments

could match.

Building Long Positions

Professional traders don’t simply buy and hope. They build positions gradually, manage risk carefully, and have

clear exit strategies. A trader anticipating higher prices might:

- Accumulate positions over weeks or months as prices remain low

- Use options to limit downside risk while maintaining upside exposure

- Set price targets for taking profits at various levels

- Monitor supply and demand indicators to validate the thesis

- Adjust position size based on conviction and risk tolerance

This disciplined approach differs from casino gambling, though the line can blur when traders become overconfident

or overleveraged.

Profiting from Price Declines

Energy traders can make money when prices fall through “short” selling—selling contracts or borrowed commodities now

with plans to buy them back cheaper later. Short positions profit from price declines but face theoretically

unlimited losses if prices rise instead.

Shorting oil before the 2020 crash generated massive profits. Traders who recognized that the pandemic would

devastate demand sold futures contracts before prices collapsed. Those who held short positions through the period

when oil briefly traded negative earned returns that seemed impossible just months earlier.

Short Selling Mechanics

Short selling in futures markets is straightforward—you simply sell contracts you don’t own, with the obligation to

buy them back before expiration or make physical delivery. In physical markets, shorting requires borrowing

commodities or entering into forward sales for production you don’t yet own.

The risks of short selling merit emphasis. While long positions can only lose 100% if prices go to zero, short

positions can suffer losses of 200%, 500%, or more if prices spike. The 2021 natural gas price surge in Europe

destroyed trading firms caught with large short positions.

Spread Trading Strategies

Rather than betting on absolute price direction, many traders focus on “spreads”—price differences between related

contracts. Spread trading can offer lower risk than outright positions because both sides of the trade respond to

similar factors.

Calendar spreads exploit price differences between contracts expiring at different times. If the March crude oil

contract trades at $75 and June at $78, a trader might buy March and sell June, betting that the $3 spread will

narrow. The trade profits if the gap shrinks, regardless of whether overall prices rise or fall.

Location and Quality Spreads

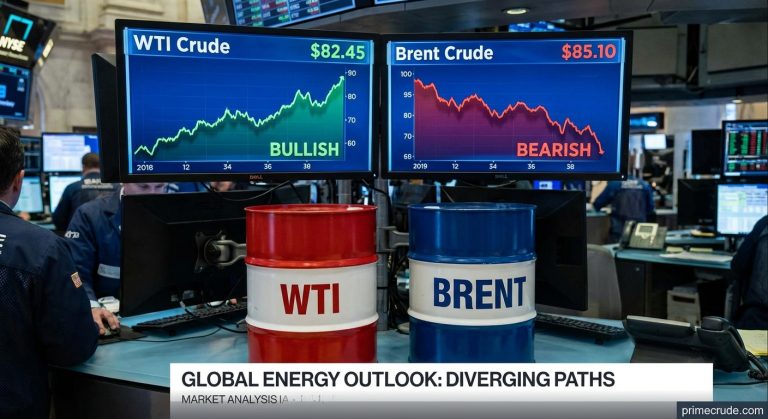

Geographic spreads capture price differences between locations. The “Brent-WTI spread”—the price difference between

North Sea Brent crude and West Texas Intermediate—fluctuates based on transportation costs, supply conditions, and

refinery demand. Traders who correctly predict spread movements profit without needing to forecast absolute price

levels.

Quality spreads reflect price differences between crude oil grades or different products. The “crack spread”

measures the relationship between crude oil prices and refined product prices, reflecting refinery margins. Trading

crack spreads lets refiners hedge their profitability or lets speculators bet on refining economics.

Volatility Trading

Some traders profit specifically from price volatility rather than price direction. Options markets allow betting

that prices will move significantly—in either direction—without requiring correct directional forecasts.

Buying “straddles”—simultaneously purchasing call and put options at the same strike price—profits if prices move

sharply up or down. The strategy loses money if prices remain stable, as the options expire worthless. This trade

effectively bets on volatility exceeding what the market expects.

Selling Volatility

Conversely, selling options generates income if prices remain stable. The seller collects premium from buyers but

faces losses if prices move sharply. This strategy works well in calm markets but can generate devastating losses

when unexpected events cause price spikes.

Natural gas markets particularly attract volatility traders. The commodity’s seasonal demand swings and weather

sensitivity create predictable periods of high volatility. Traders buy volatility before winter heating season and

sell it during calm shoulder seasons.

The Role of Information and Analysis

Successful energy trading requires deep understanding of supply and demand fundamentals. Traders analyze production

data, inventory levels, weather forecasts, economic indicators, and geopolitical developments to forecast price

movements.

Industry-specific knowledge provides trading edges. Understanding how refinery maintenance schedules affect regional

product supplies, or how pipeline constraints impact basis differentials, creates opportunities invisible to

generalist investors. This specialized expertise explains why former oil industry professionals often become

successful traders.

Real-Time Information

Speed matters in trading. News about pipeline disruptions, refinery outages, or OPEC announcements moves markets

within seconds. Major trading houses invest heavily in real-time data feeds, proprietary analytics, and systems that

can execute trades faster than competitors.

Physical traders with assets in the field gain informational advantages. A trading company that operates storage

terminals sees inventory movements before they appear in official reports. Tanker trackers monitoring vessel

positions can identify supply shifts ahead of market consensus.

Risk Management: The Essential Discipline

The difference between successful trading operations and spectacular blowups often comes down to risk management.

The energy markets that create profit opportunities can also generate losses that destroy careers, firms, or even

previously wealthy individuals.

Position sizing limits how much capital rides on any single trade. Professional trading operations typically risk

only 1-3% of capital on individual positions, ensuring that inevitable losses don’t threaten survival. Amateurs who

bet too large on single trades eventually encounter the trade that ruins them.

Stop Losses and Hedges

Stop-loss orders automatically close positions that move against traders beyond specified limits. While stops don’t

guarantee execution at desired prices during violent market moves, they impose discipline on traders who might

otherwise let losses grow.

Hedging limits exposure by establishing offsetting positions. A trader long crude oil might buy puts that profit if

prices crash, converting an outright bet into a defined-risk position. The cost of protection reduces potential

profits but prevents catastrophic losses.

Major Trading Firms and Their Approaches

Several types of organizations dominate energy trading. Understanding their different approaches reveals the

industry’s diversity.

Traditional oil trading houses—Vitol, Trafigura, Glencore, Gunvor—combine physical trading with financial positions.

These firms move actual barrels around the world, earning logistics margins while using their physical presence to

inform speculative positions. Their scale provides informational and operational advantages smaller players cannot

match.

Banks and Hedge Funds

Investment banks like Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley operate commodity trading divisions that make markets, trade

for the bank’s account, and advise clients. Post-2008 regulations limited bank risk-taking but these institutions

remain significant market participants.

Hedge funds range from energy-focused specialists to diversified macro funds that trade energy alongside other

markets. Funds like Andurand Capital have generated huge returns—and suffered significant drawdowns—from energy

bets. Their aggressive strategies and risk tolerance create market liquidity while occasionally destabilizing

prices.

Technology and Algorithmic Trading

Computer-driven trading has transformed energy markets. Algorithms execute trades based on price patterns, news

sentiment, or quantitative signals faster than humans can react. High-frequency traders profit from tiny price

discrepancies that exist for milliseconds.

Machine learning models analyze vast datasets—satellite imagery of oil storage tanks, shipping transponder data,

refinery utilization signals—to extract trading signals. These technological advantages have raised the bar for

competing through traditional analysis.

The Human Element Remains

Despite technological advances, human judgment remains essential for many trading strategies. Geopolitical analysis,

relationship-based physical trading, and crisis reaction still require experienced humans. The most successful

operations combine technological capabilities with experienced traders’ market intuition.

The Ethics and Social Impact

Energy trading raises legitimate questions about market manipulation, societal impact, and whether speculation

raises consumer prices. Traders naturally argue their activities improve market efficiency and price discovery, but

critics question whether the massive profits come at public expense.

Regulatory frameworks attempt to prevent manipulation and ensure fair markets. Position limits cap how much any

single trader can control. Reporting requirements give regulators visibility into large positions.

Manipulation—cornering markets, spreading false information, or coordinating trades—carries significant penalties.

Does Speculation Raise Prices?

Whether speculation increases commodity prices remains debated. Academic research reaches mixed conclusions. Some

studies suggest speculative activity increases short-term volatility without affecting long-term price levels.

Others find evidence that speculative flows temporarily push prices above fundamentals.

Traders argue they perform valuable functions—providing liquidity, transferring risk from producers and consumers,

and improving price discovery. Critics counter that the enormous profits extracted represent a tax on the real

economy.

Getting Started in Energy Trading

Aspiring energy traders face a challenging path. Major trading firms recruit from top universities and MBA programs,

seeking quantitative skills, market knowledge, and psychological suitability for high-pressure trading.

Career progression typically starts in support roles—analysis, operations, or risk management—before traders earn

responsibility for their own positions. Many successful traders began in the physical commodities business,

understanding supply chains before moving to financial trading.

For Individual Investors

Individual investors can access energy commodities through futures accounts, ETFs, or energy company stocks.

However, competing against professional traders with informational and technological advantages proves difficult for

amateurs.

Those interested in energy exposure might consider ETFs that provide diversified commodity positions with

professional management. Direct futures trading requires substantial capital, risk tolerance, and time commitment

that most individuals lack.

Conclusion

Energy traders profit from price swings through strategies ranging from straightforward directional bets to

sophisticated spread trades and volatility plays. Success requires deep market knowledge, disciplined risk

management, and the psychological resilience to endure inevitable losing periods.

The industry operates largely invisible to the public but significantly influences the prices we pay for fuel and

energy. Whether one views traders as essential market participants or extractive speculators, understanding their

activities illuminates how energy markets function and why prices sometimes seem disconnected from obvious supply

and demand fundamentals.

For those considering energy trading careers or investments, the potential rewards are substantial but so are the

risks. Markets that can generate fortunes can just as easily destroy them.

The energy trading world rewards those who combine market knowledge, analytical rigor, and risk

discipline—while humbling those who mistake luck for skill or leverage for wisdom.

📋 Educational Disclaimer

This article is provided for educational and informational purposes only. It does not constitute financial,

investment, or professional advice. Energy markets are complex and volatile.

Before making any investment or trading decisions, consult with qualified financial advisors who understand your

specific situation and risk tolerance. Past market performance does not guarantee future results.

The information presented here is general in nature and may not be suitable for your particular circumstances.