Energy futures contracts traded on exchanges like NYMEX and ICE move trillions of dollars annually, setting the

prices that determine what we pay for gasoline, heating oil, and natural gas. To newcomers, this world seems

intimidatingly complex—a realm of margin calls, contango, and front-month rollovers that speaks its own language.

Yet the fundamental concepts underlying futures trading are surprisingly straightforward once explained clearly. A

futures contract is simply an agreement to buy or sell a commodity at a specified price on a future date. Everything

else builds on this foundation. Understanding how energy futures work opens windows into global commodity markets

and provides tools for both speculation and hedging that sophisticated investors have used for decades. This guide

breaks down the complexity into manageable concepts that any motivated beginner can understand.

What Is a Futures Contract?

A futures contract represents a standardized agreement between two parties to exchange a specific quantity of a

commodity at a predetermined price on a specific future date. For energy futures, this might mean 1,000 barrels of

West Texas Intermediate crude oil delivered to Cushing, Oklahoma, in March, or 10,000 million BTUs of natural gas

delivered at Henry Hub in Louisiana in April.

The standardization distinguishes futures from customized forward contracts. Every WTI crude oil futures contract

traded on NYMEX specifies identical quantity, quality, delivery location, and other terms. This standardization

enables exchange trading, where anonymous buyers and sellers transact through a central marketplace.

The Two Sides of Every Trade

Every futures trade has a buyer (long) and a seller (short). The long position agrees to buy the commodity at the

specified price; the short position agrees to sell. Neither party needs to own the commodity or intend to take

delivery—most futures positions are closed before delivery through offsetting trades.

If you buy a crude oil futures contract at $75 per barrel and prices rise to $80, you can sell the contract for a $5

profit per barrel. Conversely, if prices fall to $70, you’ve lost $5 per barrel. The simplicity of this profit

calculation—buy low, sell high for longs; sell high, buy low for shorts—underlies all futures trading.

Major Energy Futures Contracts

Several energy futures contracts dominate global trading. Each has distinct characteristics suited to different

purposes, with the most actively traded enjoying excellent liquidity and tight bid-ask spreads.

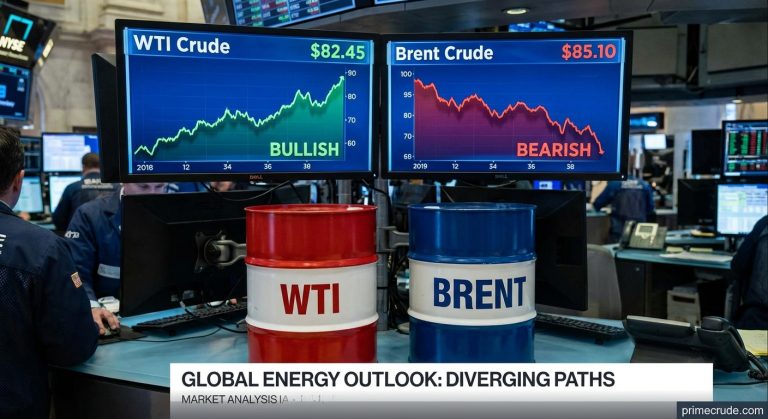

WTI Crude Oil (CL) is the benchmark American crude oil contract, representing 1,000 barrels of light sweet crude

deliverable at Cushing, Oklahoma. With typical daily volume exceeding 1 million contracts, WTI offers exceptional

liquidity for traders.

Other Major Contracts

Brent Crude Oil (BRN) serves as the international benchmark, representing North Sea crude and settling financially

rather than through physical delivery. European and Asian crude oil is typically priced relative to Brent.

Natural Gas (NG) contracts represent 10,000 million BTUs of natural gas deliverable at Henry Hub in Louisiana.

Natural gas futures are notably volatile, with prices capable of doubling or halving over months based on weather

and supply conditions.

RBOB Gasoline (RB) and Heating Oil (HO) contracts represent refined products, each covering roughly 42,000 gallons.

These contracts typically trade as spreads against crude oil, capturing refining margins rather than outright price

levels.

How Futures Markets Actually Function

Futures exchanges provide centralized marketplaces where standardized contracts trade. The CME Group (which owns

NYMEX) and ICE operate the major energy futures exchanges, processing millions of contracts daily through electronic

trading platforms.

When you place an order to buy or sell futures, it enters the exchange’s matching engine, which pairs buyers with

sellers at agreeable prices. The exchange’s clearinghouse becomes the counterparty to both sides, guaranteeing

performance and eliminating credit risk between traders.

Margin and Leverage

Futures trading uses margin—a good faith deposit representing a fraction of the contract’s value. Initial margin

requirements typically range from 5-15% of contract value, providing substantial leverage. A $75,000 crude oil

contract (1,000 barrels × $75) might require only $5,000-7,000 in margin.

This leverage amplifies both gains and losses. A 5% price move on a fully margined position represents a 50% or

greater return (or loss) on the margin. This leverage attracts speculators but can quickly generate margin calls

when positions move against traders.

| Concept | Definition | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Initial Margin | Deposit required to open position | $6,000 for one CL contract |

| Maintenance Margin | Minimum balance to keep position open | $5,500 for one CL contract |

| Margin Call | Request to add funds when below maintenance | Must deposit to return to initial margin |

| Leverage | Contract value ÷ Margin required | $75,000 ÷ $6,000 = 12.5:1 |

Understanding Contract Months and Rollovers

Unlike stocks that exist indefinitely, futures contracts expire on specific dates. Crude oil futures expire monthly;

natural gas and other contracts follow their own schedules. Traders must close or roll positions before expiration

to avoid delivery obligations.

The “front month” contract is the nearest expiration and typically the most actively traded. As expiration

approaches, traders “roll” positions to the next month by selling the expiring contract and buying the next one.

This roll involves a spread trade and may generate profit or loss depending on price differences between months.

Contango and Backwardation

When distant months trade higher than near months, the market is in “contango.” This typically reflects storage

costs—it costs money to hold physical commodities, so future delivery should cost more than immediate delivery.

When near months trade higher than distant months, the market is in “backwardation.” This occurs when immediate

supply is tight, and buyers pay premiums for near-term delivery. Backwardation often signals supply concerns or

strong current demand.

Basic Trading Strategies for Beginners

New traders should start with straightforward strategies before attempting complex spreads or option combinations.

Simple long and short positions provide clear profit and loss dynamics that teach market behavior.

Going long (buying futures) profits when prices rise. A trader expecting demand increases, supply disruptions, or

economic growth might buy crude oil futures. The risk is limited to price going to zero (unlikely for energy) but

losses can still exceed the original margin.

Short Selling

Going short (selling futures) profits when prices fall. A trader expecting weak demand, increased production, or

economic slowdown might sell natural gas futures. Short positions face theoretically unlimited risk since prices can

rise indefinitely—natural gas has briefly traded ten times its normal level during price spikes.

Beginners should understand that futures markets are zero-sum games—every dollar gained by one trader is lost by

another. This competitive environment makes consistent profits difficult without genuine information or analytical

advantages.

Spread Trading Basics

Spread trading involves simultaneous long and short positions in related contracts. These trades profit from changes

in price relationships rather than absolute price levels, offering lower risk than outright positions.

Calendar spreads involve buying one month and selling another in the same commodity. If December crude trades at $75

and January at $76, a trader might buy December and sell January, betting that the $1 spread will widen or narrow.

The position is hedged against overall price changes.

Inter-Commodity Spreads

Inter-commodity spreads involve different but related products. The “crack spread” trades crude oil against refined

products, capturing refinery economics. A trader buying crude and selling equivalent amounts of gasoline and heating

oil profits when refining margins expand.

These spread strategies require understanding the fundamental relationships between markets. Why should gasoline

trade at a certain premium to crude? What determines seasonal natural gas spreads? This analysis goes beyond simple

price forecasting.

Risk Management for Beginners

New futures traders frequently underestimate risk, over-leverage positions, and lack exit strategies. Following

basic risk management principles prevents the catastrophic losses that destroy trading capital and end trading

careers.

Position sizing is the first discipline. Risk no more than 1-3% of trading capital on any single position. With

$50,000 capital, a maximum $1,500 risk per trade allows the inevitable losses without account devastation.

Stop-Loss Orders

Stop-loss orders automatically close positions at predetermined price levels. If you buy crude at $75 with a stop at

$72, your maximum loss per contract is $3,000 (1,000 barrels × $3). This discipline prevents small losses from

becoming large ones.

However, stop losses don’t guarantee execution at stop prices. In volatile markets, prices can gap through stop

levels, resulting in fills significantly worse than intended. Understanding this limitation helps traders size

positions appropriately.

Technical vs. Fundamental Analysis

Traders use different analytical approaches to forecast price movements. Fundamental analysis examines supply and

demand factors—production levels, inventory data, economic indicators, weather forecasts—that should ultimately

determine prices.

Technical analysis studies price charts and trading patterns, assuming that historical price behavior predicts

future movements. Chart patterns, support and resistance levels, and momentum indicators provide trading signals

independent of fundamental factors.

Which Approach Works Better?

Debates about fundamental versus technical analysis continue without resolution. Many successful traders combine

both approaches—using fundamentals to establish directional bias and technicals to time entries and exits.

For beginners, understanding basic chart patterns and support/resistance concepts provides useful context without

requiring deep commodity expertise. Fundamental analysis requires industry knowledge that takes years to develop.

Common Beginner Mistakes

Experienced traders recognize patterns of failure among newcomers. Avoiding these common mistakes improves survival

odds in competitive markets.

Over-leveraging destroys accounts fastest. The ability to control $75,000 of crude oil with $6,000 margin doesn’t

mean you should. Maximum leverage means even small adverse moves trigger margin calls or forced liquidation.

Lack of Pre-Trade Planning

Entering trades without clear plans for both profit-taking and loss-cutting leads to poor decisions under pressure.

Before each trade, know your target price, stop-loss level, and position size. Write down the rationale for the

trade. This discipline prevents emotional decision-making.

Revenge trading—immediately re-entering after losses to recover—typically compounds problems. Losses hurt

emotionally, but trading to heal emotional wounds rarely succeeds. Taking breaks after losing trades allows rational

decision-making to return.

Resources for Learning More

Developing competence in futures trading requires ongoing education. Exchange websites (CME Group, ICE) provide

contract specifications, educational materials, and market data. Industry publications like Oil & Gas Investor and

Natural Gas Intelligence cover fundamental developments.

Paper trading—using simulated money—allows practice without financial risk. Most brokerage platforms offer paper

trading accounts where beginners can test strategies and learn order execution before risking real capital.

Choosing a Broker

Selecting a futures broker involves considering commission costs, platform capabilities, customer service, and

margin requirements. Major brokers like Interactive Brokers, TD Ameritrade, and specialized firms like Cannon

Trading serve retail futures traders.

Regulatory protections through CFTC oversight and customer fund segregation provide important but imperfect

safeguards. Research brokers thoroughly before entrusting funds to any firm.

From Paper Trading to Real Money

Transitioning from paper trading to real money reveals psychological factors that simulation cannot replicate. Real

losses hurt; real gains trigger greed. Managing these emotions proves at least as important as analytical skills.

Start with small positions when trading real money. Even if you could trade ten contracts, trade one or two until

you’ve established consistent profitability. Losing money with minimum position size limits damage while teaching

essential lessons.

Tracking Performance

Successful traders maintain detailed records of every trade—entry and exit prices, reasoning, market conditions,

emotional state. Reviewing this data reveals patterns of success and failure that inform improvement.

Honest self-assessment is difficult but essential. Most aspiring traders fail to achieve consistent profitability

despite effort and education. Recognizing when trading isn’t working and reducing or ceasing activity is a skill in

itself.

Conclusion

Energy futures trading offers opportunities to profit from price movements in the world’s most important commodity

markets. The standardized contracts traded on major exchanges provide transparent, liquid markets accessible to

retail traders alongside institutional participants.

Success requires understanding how futures contracts work, developing analytical frameworks for price forecasting,

implementing rigorous risk management, and maintaining psychological discipline through winning and losing periods.

Few beginners achieve consistent profitability, but those who develop genuine skills find substantial rewards.

Starting with education, progressing to paper trading, and eventually trading small real-money positions provides

structured development. Respecting the market’s ability to generate losses as easily as profits keeps perspective

throughout the journey.

Energy futures markets reward prepared, disciplined traders while punishing the overleveraged and

undereducated—understanding this reality is where successful trading careers begin.

📋 Educational Disclaimer

This article is provided for educational and informational purposes only. It does not constitute financial,

investment, or professional advice. Energy markets are complex and volatile.

Before making any investment or trading decisions, consult with qualified financial advisors who understand your

specific situation and risk tolerance. Past market performance does not guarantee future results.

The information presented here is general in nature and may not be suitable for your particular circumstances.